|

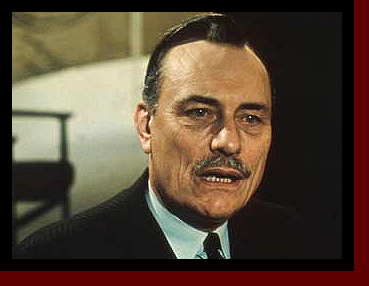

John

Enoch Powell, MBE PC (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a

British politician, classical scholar, poet, writer, linguist and

soldier. He served as a Conservative Party Member of Parliament (MP)

(1950–74), Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) MP (1974–1987), and

Minister of Health (1960–63). He attained most prominence in 1968,

when he made a controversial speech against immigration, now widely

referred to as the "Rivers of Blood" speech. In response,

he was sacked from his position as Shadow Defence Secretary (1965–68)

in the Shadow Cabinet of Edward Heath. A poll at the time suggested

that 74% of the UK population agreed with Powell's opinions and his

supporters claim that this large public following that Powell

attracted may have

helped the

Conservatives to win the 1970 general

election. Before entering politics, he had been a classical scholar,

becoming a full Professor of Ancient Greek at the age of 25. During

the Second World War, he served in both staff and intelligence

positions, reaching the rank of brigadier in his early thirties. He

also wrote poetry, his first works being published in 1937, as well

as many books on classical and political subjects. John

Enoch Powell, MBE PC (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a

British politician, classical scholar, poet, writer, linguist and

soldier. He served as a Conservative Party Member of Parliament (MP)

(1950–74), Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) MP (1974–1987), and

Minister of Health (1960–63). He attained most prominence in 1968,

when he made a controversial speech against immigration, now widely

referred to as the "Rivers of Blood" speech. In response,

he was sacked from his position as Shadow Defence Secretary (1965–68)

in the Shadow Cabinet of Edward Heath. A poll at the time suggested

that 74% of the UK population agreed with Powell's opinions and his

supporters claim that this large public following that Powell

attracted may have

helped the

Conservatives to win the 1970 general

election. Before entering politics, he had been a classical scholar,

becoming a full Professor of Ancient Greek at the age of 25. During

the Second World War, he served in both staff and intelligence

positions, reaching the rank of brigadier in his early thirties. He

also wrote poetry, his first works being published in 1937, as well

as many books on classical and political subjects.

The

Rivers of Blood speech was a controversial speech about immigration.

It was made on April 20, 1968 by the British politician Enoch

Powell. The speech took place at the annual meeting of the West

Midlands Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham, in the Midland

Hotel. In a small room after a lunch, Powell warned his audience of

what he believed would be the consequences of continued immigration

to Britain from the Commonwealth.

Below is the full text of Enoch Powell's so-called 'Rivers of Blood'

speech, which was delivered to a Conservative Association meeting in

Birmingham on April 20 1968.

The supreme

function of statesmanship is to provide against preventable evils.

In seeking to do so, it encounters obstacles which are deeply rooted

in human nature.

One is that

by the very order of things such evils are not demonstrable until

they have occurred: at each stage in their onset there is room for

doubt and for dispute whether they be real or imaginary. By the same

token, they attract little attention in comparison with current

troubles, which are both indisputable and pressing: whence the

besetting temptation of all politics to concern itself with the

immediate present at the expense of the future.

Above all,

people are disposed to mistake predicting troubles for causing

troubles and even for desiring troubles: "If only," they

love to think, "if only people wouldn't talk about it, it

probably wouldn't happen."

Perhaps this

habit goes back to the primitive belief that the word and the thing,

the name and the object, are identical.

At all

events, the discussion of future grave but, with effort now,

avoidable evils is the most unpopular and at the same time the most

necessary occupation for the politician. Those who knowingly shirk

it deserve, and not infrequently receive, the curses of those who

come after.

A week or

two ago I fell into conversation with a constituent, a middle-aged,

quite ordinary working man employed in one of our nationalised

industries.

After a

sentence or two about the weather, he suddenly said: "If I had

the money to go, I wouldn't stay in this country." I made some

deprecatory reply to the effect that even this government wouldn't

last for ever; but he took no notice, and continued: "I have

three children, all of them been through grammar school and two of

them married now, with family. I shan't be satisfied till I have

seen them all settled overseas. In this country in 15 or 20 years'

time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man."

I can

already hear the chorus of execration. How dare I say such a

horrible thing? How dare I stir up trouble and inflame feelings by

repeating such a conversation?

The answer

is that I do not have the right not to do so. Here is a decent,

ordinary fellow Englishman, who in broad daylight in my own town

says to me, his Member of Parliament, that his country will not be

worth living in for his children.

I simply do

not have the right to shrug my shoulders and think about something

else. What he is saying, thousands and hundreds of thousands are

saying and thinking - not throughout Great Britain, perhaps, but in

the areas that are already undergoing the total transformation to

which there is no parallel in a thousand years of English history.

In 15 or 20

years, on present trends, there will be in this country three and a

half million Commonwealth immigrants and their descendants. That is

not my figure. That is the official figure given to parliament by

the spokesman of the Registrar General's Office.

There is no

comparable official figure for the year 2000, but it must be in the

region of five to seven million, approximately one-tenth of the

whole population, and approaching that of Greater London. Of course,

it will not be evenly distributed from Margate to Aberystwyth and

from Penzance to Aberdeen. Whole areas, towns and parts of towns

across England will be occupied by sections of the immigrant and

immigrant-descended population.

As time goes

on, the proportion of this total who are immigrant descendants,

those born in England, who arrived here by exactly the same route as

the rest of us, will rapidly increase. Already by 1985 the

native-born would constitute the majority. It is this fact which

creates the extreme urgency of action now, of just that kind of

action which is hardest for politicians to take, action where the

difficulties lie in the present but the evils to be prevented or

minimised lie several parliaments ahead.

The natural

and rational first question with a nation confronted by such a

prospect is to ask: "How can its dimensions be reduced?"

Granted it be not wholly preventable, can it be limited, bearing in

mind that numbers are of the essence: the significance and

consequences of an alien element introduced into a country or

population are profoundly different according to whether that

element is 1 per cent or 10 per cent.

The answers

to the simple and rational question are equally simple and rational:

by stopping, or virtually stopping, further inflow, and by promoting

the maximum outflow. Both answers are part of the official policy of

the Conservative Party.

It almost

passes belief that at this moment 20 or 30 additional immigrant

children are arriving from overseas in Wolverhampton alone every

week - and that means 15 or 20 additional families a decade or two

hence. Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We

must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual

inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the

material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population.

It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own

funeral pyre. So insane are we that we actually permit unmarried

persons to immigrate for the purpose of founding a family with

spouses and fiancés whom they have never seen.

Let no one

suppose that the flow of dependants will automatically tail off. On

the contrary, even at the present admission rate of only 5,000 a

year by voucher, there is sufficient for a further 25,000 dependants

per annum ad infinitum, without taking into account the huge

reservoir of existing relations in this country - and I am making no

allowance at all for fraudulent entry. In these circumstances

nothing will suffice but that the total inflow for settlement should

be reduced at once to negligible proportions, and that the necessary

legislative and administrative measures be taken without delay.

I stress the

words "for settlement." This has nothing to do with the

entry of Commonwealth citizens, any more than of aliens, into this

country, for the purposes of study or of improving their

qualifications, like (for instance) the Commonwealth doctors who, to

the advantage of their own countries, have enabled our hospital

service to be expanded faster than would otherwise have been

possible. They are not, and never have been, immigrants.

I turn to

re-emigration. If all immigration ended tomorrow, the rate of growth

of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population would be

substantially reduced, but the prospective size of this element in

the population would still leave the basic character of the national

danger unaffected. This can only be tackled while a considerable

proportion of the total still comprises persons who entered this

country during the last ten years or so.

Hence the

urgency of implementing now the second element of the Conservative

Party's policy: the encouragement of re-emigration.

Nobody can

make an estimate of the numbers which, with generous assistance,

would choose either to return to their countries of origin or to go

to other countries anxious to receive the manpower and the skills

they represent.

Nobody

knows, because no such policy has yet been attempted. I can only say

that, even at present, immigrants in my own constituency from time

to time come to me, asking if I can find them assistance to return

home. If such a policy were adopted and pursued with the

determination which the gravity of the alternative justifies, the

resultant outflow could appreciably alter the prospects.

The third

element of the Conservative Party's policy is that all who are in

this country as citizens should be equal before the law and that

there shall be no discrimination or difference made between them by

public authority. As Mr Heath has put it we will have no

"first-class citizens" and "second-class

citizens." This does not mean that the immigrant and his

descendent should be elevated into a privileged or special class or

that the citizen should be denied his right to discriminate in the

management of his own affairs between one fellow-citizen and another

or that he should be subjected to imposition as to his reasons and

motive for behaving in one lawful manner rather than another.

There could

be no grosser misconception of the realities than is entertained by

those who vociferously demand legislation as they call it

"against discrimination", whether they be leader-writers

of the same kidney and sometimes on the same newspapers which year

after year in the 1930s tried to blind this country to the rising

peril which confronted it, or archbishops who live in palaces,

faring delicately with the bedclothes pulled right up over their

heads. They have got it exactly and diametrically wrong.

The

discrimination and the deprivation, the sense of alarm and of

resentment, lies not with the immigrant population but with those

among whom they have come and are still coming.

This is why

to enact legislation of the kind before parliament at this moment is

to risk throwing a match on to gunpowder. The kindest thing that can

be said about those who propose and support it is that they know not

what they do.

Nothing is

more misleading than comparison between the Commonwealth immigrant

in Britain and the American Negro. The Negro population of the

United States, which was already in existence before the United

States became a nation, started literally as slaves and were later

given the franchise and other rights of citizenship, to the exercise

of which they have only gradually and still incompletely come. The

Commonwealth immigrant came to Britain as a full citizen, to a

country which knew no discrimination between one citizen and

another, and he entered instantly into the possession of the rights

of every citizen, from the vote to free treatment under the National

Health Service.

Whatever

drawbacks attended the immigrants arose not from the law or from

public policy or from administration, but from those personal

circumstances and accidents which cause, and always will cause, the

fortunes and experience of one man to be different from another's.

But while,

to the immigrant, entry to this country was admission to privileges

and opportunities eagerly sought, the impact upon the existing

population was very different. For reasons which they could not

comprehend, and in pursuance of a decision by default, on which they

were never consulted, they found themselves made strangers in their

own country.

They found

their wives unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their

children unable to obtain school places, their homes and

neighbourhoods changed beyond recognition, their plans and prospects

for the future defeated; at work they found that employers hesitated

to apply to the immigrant worker the standards of discipline and

competence required of the native-born worker; they began to hear,

as time went by, more and more voices which told them that they were

now the unwanted. They now learn that a one-way privilege is to be

established by act of parliament; a law which cannot, and is not

intended to, operate to protect them or redress their grievances is

to be enacted to give the stranger, the disgruntled and the

agent-provocateur the power to pillory them for their private

actions.

In the

hundreds upon hundreds of letters I received when I last spoke on

this subject two or three months ago, there was one striking feature

which was largely new and which I find ominous. All Members of

Parliament are used to the typical anonymous correspondent; but what

surprised and alarmed me was the high proportion of ordinary,

decent, sensible people, writing a rational and often well-educated

letter, who believed that they had to omit their address because it

was dangerous to have committed themselves to paper to a Member of

Parliament agreeing with the views I had expressed, and that they

would risk penalties or reprisals if they were known to have done

so. The sense of being a persecuted minority which is growing among

ordinary English people in the areas of the country which are

affected is something that those without direct experience can

hardly imagine.

I am going

to allow just one of those hundreds of people to speak for me:

“Eight

years ago in a respectable street in Wolverhampton a house was sold

to a Negro. Now only one white (a woman old-age pensioner) lives

there. This is her story. She lost her husband and both her sons in

the war. So she turned her seven-roomed house, her only asset, into

a boarding house. She worked hard and did well, paid off her

mortgage and began to put something by for her old age. Then the

immigrants moved in. With growing fear, she saw one house after

another taken over. The quiet street became a place of noise and

confusion. Regretfully, her white tenants moved out.

“The day

after the last one left, she was awakened at 7am by two Negroes who

wanted to use her 'phone to contact their employer. When she

refused, as she would have refused any stranger at such an hour, she

was abused and feared she would have been attacked but for the chain

on her door. Immigrant families have tried to rent rooms in her

house, but she always refused. Her little store of money went, and

after paying rates, she has less than £2 per week. “She went to

apply for a rate reduction and was seen by a young girl, who on

hearing she had a seven-roomed house, suggested she should let part

of it. When she said the only people she could get were Negroes, the

girl said, "Racial prejudice won't get you anywhere in this

country." So she went home.

“The

telephone is her lifeline. Her family pay the bill, and help her out

as best they can. Immigrants have offered to buy her house - at a

price which the prospective landlord would be able to recover from

his tenants in weeks, or at most a few months. She is becoming

afraid to go out. Windows are broken. She finds excreta pushed

through her letter box. When she goes to the shops, she is followed

by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies. They cannot speak

English, but one word they know. "Racialist," they chant.

When the new Race Relations Bill is passed, this woman is convinced

she will go to prison. And is she so wrong? I begin to wonder.”

The other

dangerous delusion from which those who are wilfully or otherwise

blind to realities suffer, is summed up in the word

"integration." To be integrated into a population means to

become for all practical purposes indistinguishable from its other

members.

Now, at all

times, where there are marked physical differences, especially of

colour, integration is difficult though, over a period, not

impossible. There are among the Commonwealth immigrants who have

come to live here in the last fifteen years or so, many thousands

whose wish and purpose is to be integrated and whose every thought

and endeavour is bent in that direction.

But to

imagine that such a thing enters the heads of a great and growing

majority of immigrants and their descendants is a ludicrous

misconception, and a dangerous one.

We are on

the verge here of a change. Hitherto it has been force of

circumstance and of background which has rendered the very idea of

integration inaccessible to the greater part of the immigrant

population - that they never conceived or intended such a thing, and

that their numbers and physical concentration meant the pressures

towards integration which normally bear upon any small minority did

not operate.

Now we are

seeing the growth of positive forces acting against integration, of

vested interests in the preservation and sharpening of racial and

religious differences, with a view to the exercise of actual

domination, first over fellow-immigrants and then over the rest of

the population. The cloud no bigger than a man's hand, that can so

rapidly overcast the sky, has been visible recently in Wolverhampton

and has shown signs of spreading quickly. The words I am about to

use, verbatim as they appeared in the local press on 17 February,

are not mine, but those of a Labour Member of Parliament who is a

minister in the present government:

'The Sikh

communities' campaign to maintain customs inappropriate in Britain

is much to be regretted. Working in Britain, particularly in the

public services, they should be prepared to accept the terms and

conditions of their employment. To claim special communal rights (or

should one say rites?) leads to a dangerous fragmentation within

society. This communalism is a canker; whether practised by one

colour or another it is to be strongly condemned.'

All credit

to John Stonehouse for having had the insight to perceive that, and

the courage to say it.

For these

dangerous and divisive elements the legislation proposed in the Race

Relations Bill is the very pabulum they need to flourish. Here is

the means of showing that the immigrant communities can organise to

consolidate their members, to agitate and campaign against their

fellow citizens, and to overawe and dominate the rest with the legal

weapons which the ignorant and the ill-informed have provided. As I

look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to

see "the River Tiber foaming with much blood."

That tragic

and intractable phenomenon which we watch with horror on the other

side of the Atlantic but which there is interwoven with the history

and existence of the States itself, is coming upon us here by our

own volition and our own neglect. Indeed, it has all but come. In

numerical terms, it will be of American proportions long before the

end of the century.

Only

resolute and urgent action will avert it even now. Whether there

will be the public will to demand and obtain that action, I do not

know. All I know is that to see, and not to speak, would be the

great betrayal.

|

![]()